Transcendent Creations: The multiple life cycles of pre-colonial objects of Mesoamerica from “before dawn” to the present

This four-part spotlight series essay curated by James Deavenport, PhD, highlights objects from the Vilcek Foundation’s collection of pre-colonial or pre-Columbian artistic works originating in Mesoamerica. It seeks to put these creations into context with each other and with Mesoamerican conceptions of time and space. In addition, this analysis seeks to demonstrate links between cultures of the past and the present, exploring how these works have continued to inspire and provoke deep contemplation in the contemporary world, impacting global trends and notions of art, architecture, and identity to this day.

The Four Suns: One Mesoamerican Creation Narrative Among Many

While Mesoamerica and the pre-colonial Americas more broadly have always been an incredibly diverse space, different cultures throughout the area have created works with similar visual forms, or “languages.” These works convey the existence of shared ideas or beliefs about the creation of the world or universe across cultures, with kindred cosmologies and conceptions of time.

One of these cycles of beliefs expressed by the K’iche’ Maya has been preserved in a text called the Popol Vuh. This text contains narratives similar to those expressed through visual traditions. These include the idea that our current world was preceded by three other fallen suns and destroyed each time. Thus, the world we know is the fourth creation of the universe.

The Maya and other Mesoamericans such as those of the Mexica (also known as the Aztec Empire or Triple Alliance, who believed there had been five suns) sought to recapture some of this spiritual energy. By creating objects like the ones in this analysis, engaging forms established in earlier eras, these artists believed they could manifest the prosperity they associated with these “fallen suns” and “pre-dawn” eras.

Many pre-colonial Mesoamericans believed the precarious balance of existence was only maintained through the ritual sacrifice of human blood, thus ensuring creation, life, and civilization would endure. As a result, many of these and other pre-colonial Mesoamerican works incorporate and express rituals associated with such beliefs. Similar ideas concerning sacrifice, death, and rebirth have been shared in various ways among many human societies over time, including the Roman Catholic Christianity brought by colonial priests, settlers, and Spanish authorities, beginning in the late 15th century CE, which is especially associated with the professed belief in the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Four Time Periods or Eras

Based on the “four suns” outlined in the K’iche’ Maya text known as the Popol Vuh, this analysis is divided into four eras; in doing so, this analysis connects the “four creations” described by this Maya text with contemporary archaeological and academic periodization of Mesoamerican works of art, as outlined below:

- The First Sun and Corresponding Archaeological Timeframe: Pre-Classic ~2000 BCE–200 CE

- The Second Sun and Corresponding Archaeological Timeframe: Classic ~200–900 CE

- The Third Sun and Corresponding Archaeological Timeframe: Post-Classic ~900 CE–1492 CE

- The Fourth Sun and Corresponding Archaeological Timeframe: Colonial–Contemporary Eras ~1492–Present

While these are not meant to precisely align, they invite the viewer to consider ways of viewing time that are nonwestern and nonlinear, but rather cyclical. Ultimately, this approach reminds us that all history is interconnected and that our historical eras and periods are similarly imagined and constructed. It also invites the reader to consider the diversity of indigenous belief systems as well as the many variations of even one narrative or tradition.

From left to right: Teotihuacan Mask; Teotihuacan Mask; contemporary work, for reference; Aztec (Mexica) Life-Sized Head; and an Olmec Head mural in Chicano Park, Barrio Logan, San Diego, California. Together, these four works provide an example of the maintenance, appropriation, and refashioning of some forms of Mesoamerican visual culture across time from the first sun or “Pre-Classic” era (around 2000 BCE) to the fourth sun or “Modern/Contemporary” era (around 1492 CE–present).

Part I

The First Sun and Corresponding Archaeological Timeframe: Pre-Classic ~ 2000 BCE–200 CE

“Then was the creation and the formation. Of earth, of mud, they made [man’s] flesh. But they saw that it was not good. It melted away, it was soft, did not move, had no strength, it fell down, it was limp, it could not move its head, its face fell to one side, its sight was blurred, it could not look behind. At first it spoke, but had no mind. Quickly it soaked in the water and could not stand.” (Goetz, Delia, and Sylvanus Griswold Morley. The Book of the People = Popol Vuh: the National Book of the Ancient Quiché Maya. Printed for the Members of the Limited Editions Club at the Plantin Press, 1954. Pg. 9)

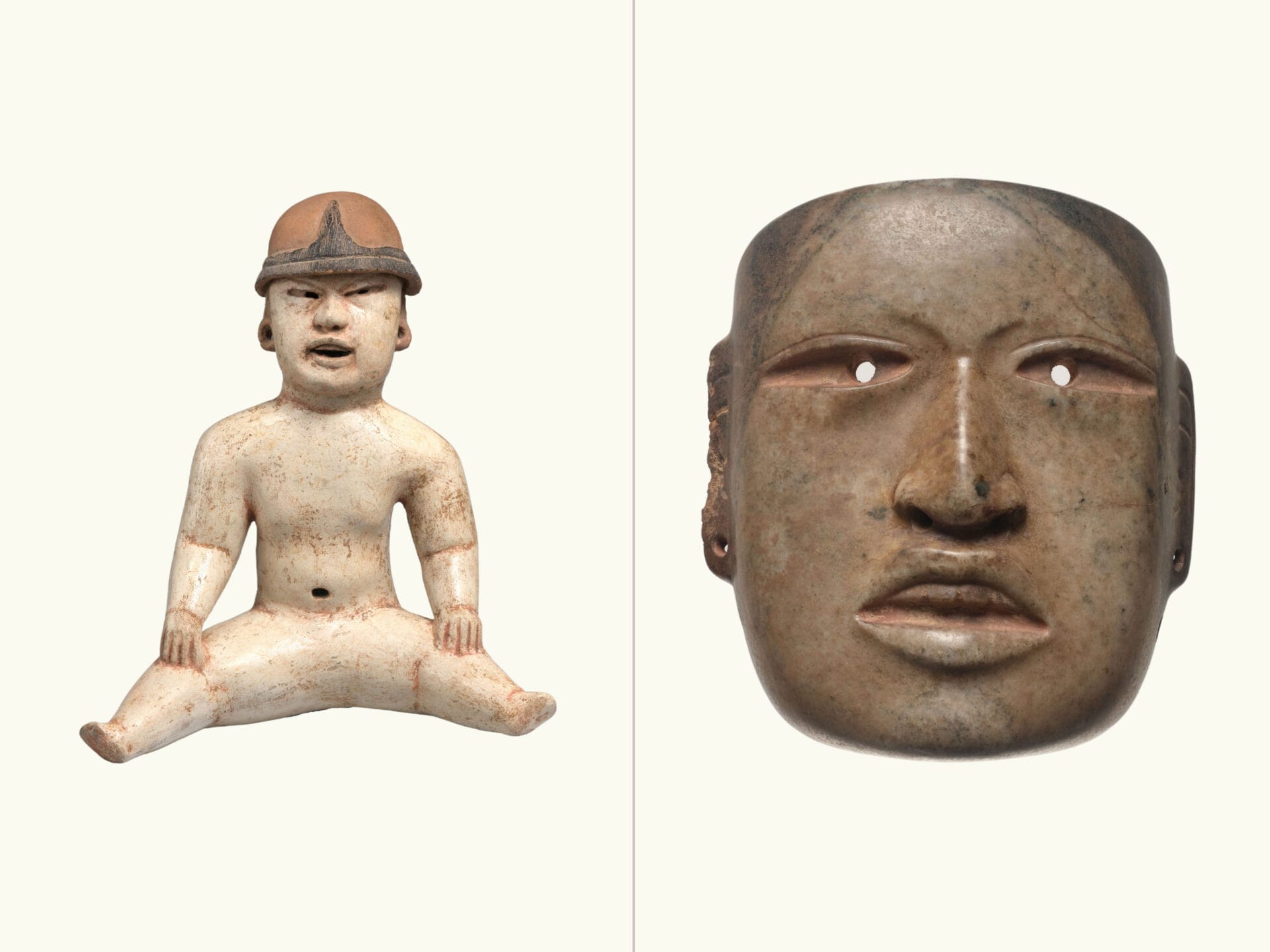

This Olmec Figure (above left) wears an emblematic helmet or headdress similar to the famous and colossal Olmec head statues. The figure may also represent the “Werejaguar” or be associated with “crocodilians” that were believed to be intimately connected to the cycles of life, death, and rebirth, which later Mesoamericans associated with sustaining the sun. Indeed, the two images above may represent the same deity or even a blending of deities.

This Olmec Mask (above right) is intimately connected both to the stylistic representation of the seated figure, and also to broader Mesoamerican representational forms that remained emblematic until the colonization by Spain in the 16th century CE. The mask also evokes the green jade stone seen as possessing great spiritual and cultural power or energy that emanated from these “pre-dawn” eras.

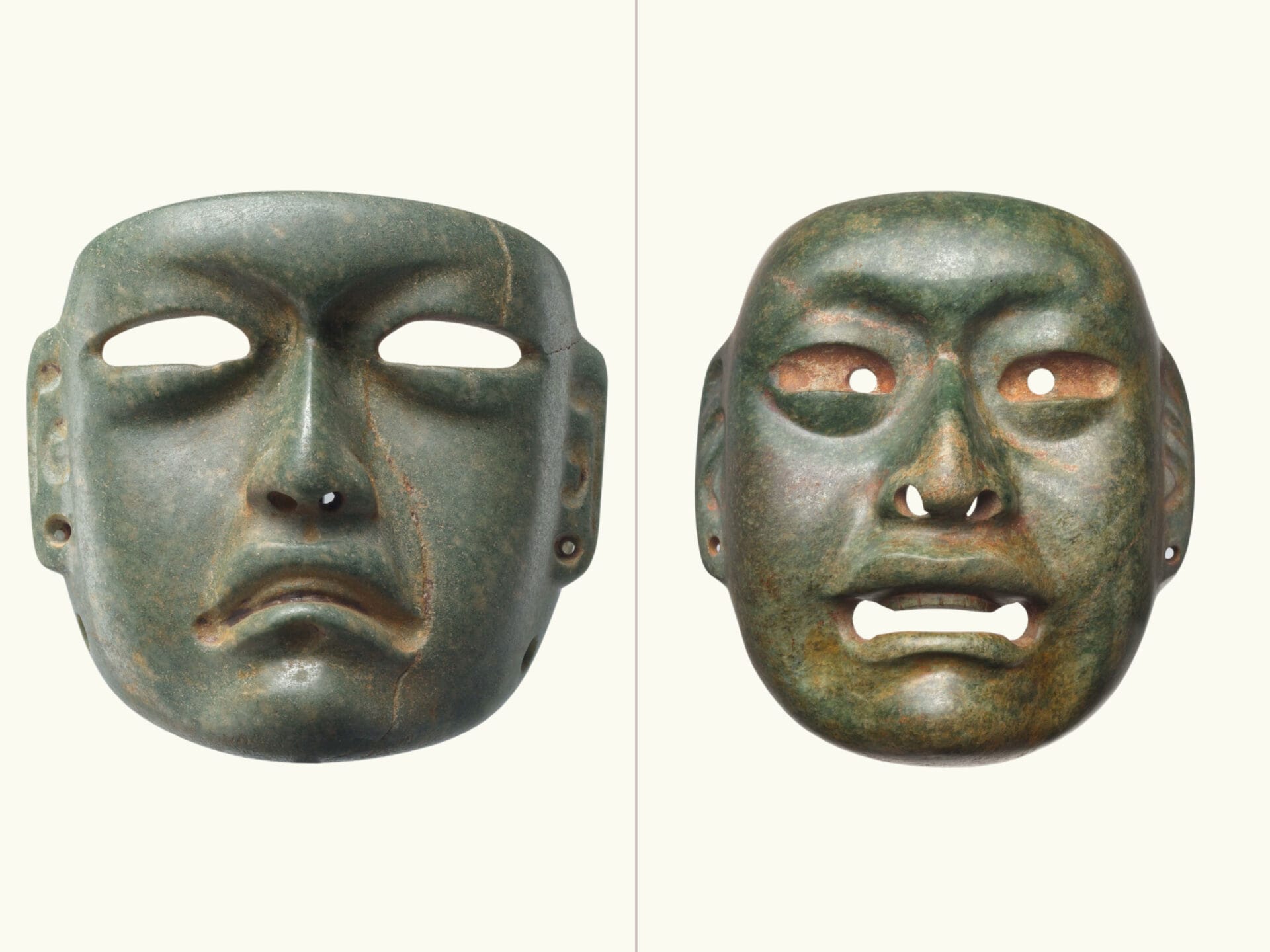

This realistic Olmec Mask (above left) continues this tradition of spiritual and cultural representation seen in the previous Olmec faces, since the green color of this stone would have been greatly venerated and prized. The hollowed-out eyes may indicate that the mask could be worn during rituals or as a death mask, to aid a revered deceased person into the afterlife.

This Olmec Mask (above right) also demonstrates the continuation of this tradition along with realistic features that similarly incorporate natural differences in the pigmentation of the stone to accentuate the facial features. The drilled openings in mouth, nostrils, and eyes also indicate this may have been worn in important rituals or as a death mask. Such representations would become “visual templates” that later cultures continued to appropriate and refashion in spectacular ways that may relate to the transformations during various stages in both human and agricultural life cycles.

Examples of such transformations or revisioning of these materials can be seen in both of these Maya Carved Plaques (above left and right). Both objects originated in Tikal (or Yax Mutal) and were fashioned from Olmec heirlooms. As celts, or axes, both of these objects were likely associated with rituals tied to sacrifice and the life cycle. Tools and traditions such as these would have helped pass on critical social and agricultural knowledge. This likely contributed to the care—or rediscovery and reuse—of these works by the Maya, who carved into them representational human and spiritual figures that allowed people to connect with and feel a part of creation.

Similar to the previous pair of objects (the Olmec celts refashioned by Maya at Tikal), the Olmec Snuffing Tablet “Spoon” (above left) as well as the Olmec Spoon (above right) were also fashioned from older celts. Both of these objects are associated with the ritual use of hallucinogens. Such celts are also associated with sacrifice, seen by many Mesoamerican cultures as an important tool and tradition for maintaining cosmic and ecological balance. The Olmec Spoon is engraved with the glyph for the god Cipactli. As Cipactli was believed by the Tlascan people to represent the chaos and a version of earth that existed prior to the creation of the current universe, this object may have been an attempt to allow the user to connect with this spiritual force and between various moments of creation.

The Olmec Standing Figure (above left) and the Chontal Figure (above right) together reveal the use of smaller, more intimate creations and charms that might be used by people in daily life, in their homes, and associated with burials as well. The similar visual styles between Olmec and Chontal figures demonstrate the trade and communication networks that linked the “Olmec heartland” in what is today Veracruz with western Mexico, in this case the state of Guerrero, especially along the Balsas River basin, which links the region with central Mexico and the Gulf of Mexico.

The Olmec-Guerrero Standing Figure (above left) and the Mezcala Standing Female Figure (above right) together reveal the overlapping stylistic similarities of these works, especially evident in the face, use of materials, and stance. The similarity of the visual forms used in their art and objects demonstrates that these two distinct cultures were in communication with each other. Both also incorporated such prestige objects to support their temporal or political power. These consistencies in artistic tradition and purpose demonstrate the potency of these forms and ideas outside of the original “Olmec heartland.” The variations of form and style in the Mezcala figure reveals that, while Mezcala artists had access to Olmec techniques and materials, they continued to appropriate and refashion, incorporating their own cultural ideas and visual forms from around Mesoamerica often associated with rebirth and transformation.

Transformation associated with creation and power over life and death was a central component of Mesoamerican and many other past societies. The Olmec Face Panel (above left) as well as the Olmec Standing Figure (above right) memorialize a representation of a moment of transition between the form and body of a human and of a jaguar. In some Mesoamerican societies, individuals sought to experience such transitions by connecting with (super-) natural forces, sometimes with the aid of hallucinogenic substances. The open mouths and prominent teeth in these objects are stylistically related to the open mouths of Olmec masks. The polished green jadeite stone used in both of these objects likely originated in what is today Guatemala; this indicates trade and cultural interaction across these regions at the time of their creation.

Teotihuacan/Western Mexico: Mezcala-Chontal, Jalisco, and Chinesco

The Teotihuacan Mask (above left) demonstrates another example of this moment of metamorphosis between human and jaguar form, as created by Teotihuacan artisans. A famous urban and ceremonial center, Teotihuaca is believed to have been a hub with connections to both the Maya and Mexica cultures. The inlaid eyes of the Teotihuacan Mask further demonstrate the skills of artists of the era, and the use of different materials to denote aspects of power or spirituality.

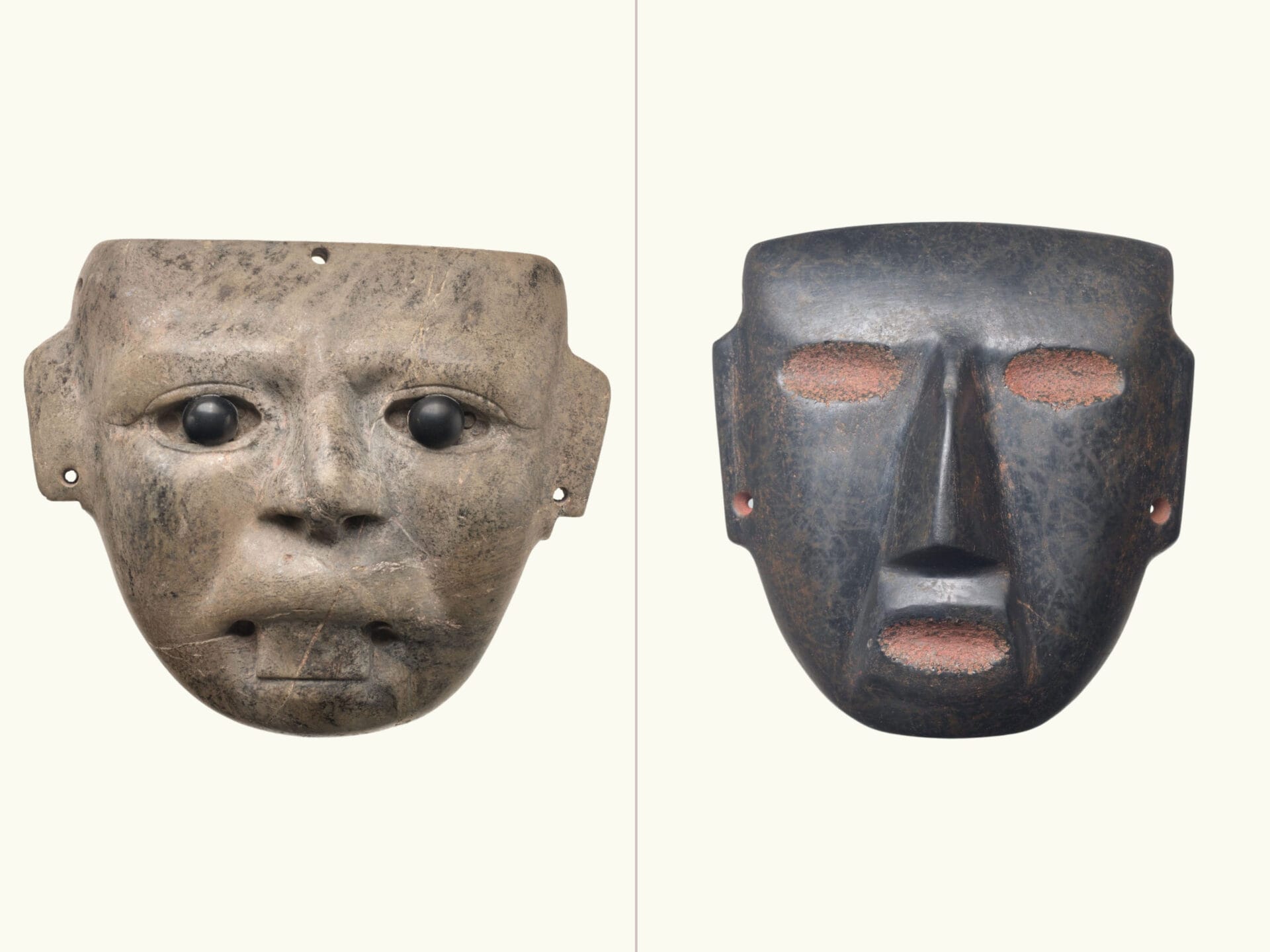

Such Teotihuacan forms borrow from Olmec antecedents; in the pairing above, they also demonstrate the interaction and reinterpretation between Teotihuacan artists and artists from Mezcala-Chontal, who created the Mezcala-Chontal Mask (above right). The red hue on the eyes, mouth, and earlobes evokes blood, and connotes fertility and cycles of life. Both masks were likely associated with funerary rituals, serving to help usher an individual along their spiritual journey and transformation beyond this life.

The Mezcala-Chontal Mask (above left) also demonstrates artists’ stylistic representation of human features using stone inlay. The detail of the eyes in this piece, paired with the more simplified and abstracted features of the face, reveals the ways people across what is today the state of Guerrero reinterpreted and sought to represent their own unique beliefs and traditions related to fertility and the afterlife.

An example of reinterpreting broader Mesoamerican visual traditions is the Mezcala-Chontal Standing Figure (above right), which many scholars argue is intimately connected with Teotihuacan (and Olmec) visual culture. The features of this particular figure, though abstracted, are accentuated with carving details used to render the eyes, the open mouth, and the ears. This figure was likely hewn from an earlier hand axe that was seen to possess great ceremonial and spiritual power tied to creation and managing the cycles of life, death, and rebirth.

The Seated Figure With Small Child (Probably Jalisco) (above left) and the Jalisco Dancer (above right) are both ceramic objects, likely created as burial offerings. Based on their style and characteristics, they are associated with the shaft tomb traditions that are believed to have been common across some areas of western Mexico roughly between 300 BCE and 400 CE. The adult figure and infant in the object depicted here on the left may represent particular individuals, or they may represent more general spiritual understandings concerning the cycles of life across generations; the adult figure’s headdress and necklace likely denote a particular social status.

The Jalisco Dancer (above right) in canine headdress with rattle and fan demonstrates a moment of dancing and transformation that represents a transcendent moment between the human and the divine, the physical and the spiritual, and life and death. Crafted using a mold, figures like this one could be mass produced; objects with similar characteristics of production are known to have been connected to Teotihuacan. Such similarities reveal potential links between cultures within the region that are—by some scholars—perceived to have been independent of one another, rather than engaging in dialogue and cultural exchange.

Similar to the two previous objects, the Chinesco (or Nayarit) Seated Figure (above) is likely a funerary object that would have been buried with a revered family or community member. Like the other works associated with shaft tomb burial traditions across western Mexico, it is believed to have been used as an aid to facilitate the deceased’s journey to the afterlife. The particular stylistic features of this work (the tattoos and possible cranial modification) link it to the ancient site of Ixtlán del Río, in Nayarit, an important source of obsidian that was used to fashion tools related to hunting and survival, warfare, and spirituality.

Part II

The Second Sun and Corresponding Archaeological Timeframe: Classic ~200–900 CE

“Do it thus and we shall know if we are to make, or carve, his mouth and eyes out of wood.” … And instantly the figures were made of wood. They looked like men, talked like men, and populated the surface of the earth … [but], they no longer thought of their Creator nor their Maker. … Immediately the wooden figures were annihilated, destroyed, broken up, and killed. A flood … was formed which fell on the heads of the wooden creatures.”

The first part of this analysis, Transcendent Creations: The First Sun, highlighted Mesoamerican works of art from the Vilcek Collection created during the “pre-Classic” period as defined by archaeologists, between approximately 2000 BCE and 200 CE, and the era presumed to roughly correspond to the cultural era of the “first sun” as outlined in the Maya text, the Popol Vuh.

This second part of this analysis explores works of art created during the “Classic” period as defined by archaeologists, between 200 CE and 900 CE. In parallel to the first portion of this analysis, the work of this era is analyzed through the lens of the cultural concept of the “Second sun” as outlined in the Popol Vuh.

Maya

As with the articles examined in the first part of this essay, in this portion of Transcendent Creations relationships between objects of art and the cultures and contexts in which they were created will be examined. Objects will be put into further context in comparison with one another, to draw out similarities and distinctions in style, interpretation, and media used by artists during the “Classic” period.

The Maya Mask of Sun God (above left) reveals similarities to earlier Mesoamerican works explored in the first part of Transcendent Creations, and ways in which artworks created by Maya artists engage similar visual and expressive traditions across time. The open mouth and protruding tongue of the subject are reminiscent of the Teotihuacan Mask. The work’s connection to the sun god K’inich Ahau is revealed through stylistic traditions engaged by Maya artists in rendering K’inich Ahau, including the aquiline nose, open mouth, and extended tongue. These traditions are also associated with renderings of Itzamna or God D, a creator god believed to rule in the sky. These affiliations reveal deep connections between Maya beliefs and cultural artifacts with agricultural cycles on sun- and water-dependent crops like corn and maize.

The Veracruz Maya Yoke with Depiction of an Anthropomorphic Effigy Figure (above right) shares features with the mask of K’inich Ahau as well as with Olmec and Teotihuacan styles, indicating similar systems of beliefs and representational styles. This sculpture is a representation of the cloth yokes that Mesoamerican athletes would wear around their waists as protective equipment while playing a Mesoamerican ball game. In the game, ballplayers would compete in teams to propel a solid rubber ball through a stone ring. In classical Maya, the game is known as pitz; in English, it is often called pok-a-tok, an adaptation of the Yucatec Maya word pokolpok. This game was played in large courts and held great ritual importance. Indeed, in the Maya text Popol Vuh, gods were said to have played this game before the creation of the world; as such, the game took on a profound importance, associated with sacrifice, fertility, and the underworld.

These Maya stone hachas are believed to be sculptural representations of the clothing and adornments worn by Maya athletes playing ritual ball games. The name hacha is taken from the Spanish word for hand-axe. Athletes are believed to have worn U-shaped yokes around their waists made of cloth and fiber, similar to the Veracruz Maya Yoke shown above, along with hacha like these, and armbands. Given the weight of these stone objects, some scholars believe that stone hacha like these and the stone yoke above are simply representations or interpretations of the actual items that ballplayers would have worn in game play. Given the ritual importance of these games in Veracruz Maya culture, hacha and yoke objects are believed to have been decorated with representations of deities and animals that held symbolic meaning to the Maya, including bats, canines, birds, serpents, and jaguars.

Left to right, the five hacha shown here depict heads and faces with anthropomorphic qualities associated with the Maya pantheon. The hacha at the top left (Maya Hacha) reveals features resembling a parrot (an animal associated in Maya culture with the sun and creation) and a serpent (an animal associated with rebirth). The top center hacha (Veracruz Maya Hacha) has a canine or bat’s head with anthropomorphic features; in Maya culture, dogs were believed to guide individuals to the underworld, and bats symbolized messengers between the living and the deceased. The hacha at the top right (Maya Hacha of God Head with Human Face) has a pronounced lip or “mustache” above the figure’s lower lip; this representation is connected to Olmec and other earlier Mesoamerican representations of Tlaloc, a god affiliated with fertility and maize. The hacha at the bottom left (Maya Hacha) represents a human-avian figure, indicating connections with the sun. The hacha at the bottom right (Veracruz Maya Hacha) depicts a human face in profile, topped with the head of an animal resembling a bird or a serpent—animals affiliated with the sun, solar cycles, life, and rebirth. Together, this particular group of hacha demonstrates the important role that animals and the natural world played in the Veracruz Maya’s conceptions of life, death, and transformation.

Teotihuacan

The Mesoamerican ball game referred to above had many iterations throughout different regions and cultures in Mesoamerica. The ceramic Teotihuacan Kneeling Ballplayer Figure holding a head or hacha (above) reveals one of the ways in which ballplayers from the region around Teotihuaca at the time of this work’s creation might have been attired. The figure shown here is depicted as wearing a yoke around the waist, knee pads, and bands around the wrists. The necklace, earplugs, and hairstyle of this figure may not have been particular to the sport, but likely hold other cultural significance, regarding the player’s status, area of origin, or style. The figure is shown holding a head, or a hacha representing a human or anthropomorphic head.

Similar to the figures represented in the five hacha above, this figural representation (Teotihuacan Goddess/God of Fertility) of a deity associated with fertility in Teotihuacan culture shares representational styles with other deities. The carvings around the figure’s mouth are similar to those of Mesoamerican rain and fertility deities, including Tlaloc. The figure is depicted as wearing a headdress of quetzal feathers; quetzal held enormous significance in cultures throughout Mesoamerica, and are another representation of the links between Mesoamerican and Maya cultural beliefs and the natural world.

The Teotihuacan Standing Figure and Masks (left to right: Teotihuacan Mask, Teotihuacan Mask, & Teotihuacan Mask) shown above—as with all the works in this portion of Transcendent Creations—were all created between 200 and 900 CE; however, these four works are deeply reminiscent of art and artifacts from the Olmec civilization, which proliferated between 1200 BCE and 400 BCE. Despite the variations in the qualities of the stone used in these four sculptures, the faces themselves are nearly identical, demonstrating the power and the endurance of such representations across centuries. Figures and masks such as these may have been used in rituals conducted in temples, however, masks such as the three at the right, above, may have been affiliated with personal use, as funerary accoutrements to help the deceased make the transition between the mortal world and the afterlife. In some Mesoamerican traditions, green stone held special significance, and was believed to represent cosmic energy from the creation of the universe and the power needed to sustain it.

Mezcala

The Mezcala culture is the name given to a Mesoamerican culture based in the Balsas River region of Mexico. It is believed to have originated between 700 and 200 BCE, but continued into the Classic period, having overlap with Teotihuacan. The Mezcala Temple (above left) and Mezcala Standing Figure (above right) demonstrate technical and ritual or ideological links between this region and Mesoamerica more broadly. The temple represents an architectural structure, and features a recumbent figure lying atop the upper horizontal plane of the sculpture; this horizontal plinth is adorned with a circular motif, which may represent the sun or the moon element of the cosmos. Figures on objects such as this have been interpreted as being representative of priests, as individuals gazing at the stars or cosmos, or human sacrifices. The combination of cosmic themes and man-made elements speak to the complexities of ritual, culture, and the built and natural environment. The celestial motif also suggests a potential connection between the solar or lunar calendar and rituals or days of importance to the Mezcala people, with the positioning of the “stargazing” figure above this element holding a particular relevance.

The Mezcala standing figure (above right) is hewn of a similarly colored stone to the temple. The figure’s facial features are carved similarly to those of the figure atop the temple (above left), with a horizontal ridge defining the eyebrows and eye sockets, and the nose. The slashes representing the figure’s arms also recall the style invoked in earlier works of art, like the Mezcala-Chontal Standing Figure. The similarly crafted standing figure (above right) reveals stylistic connections with the Olmec and Teotihuacan. Given the size and the material employed in the figure, it is presumed that this work—like some others of this period—may have been carved from a pre-existing hand axe or celt from an earlier culture.

The Mezcala Temple (above left) and Mezcala Figure (above right) are both carved from stone and, as with the above pairing, the figure atop this temple’s uppermost horizontal plane and the figure are similarly carved, with deep horizontal grooves below the eyebrows and a geometric oblong indentation representing the figure’s mouth. Both figures have arms folded and crossed against the torso. This positioning of the arms indicates that these sculptures may have had some association with death and burials. In both of these sculptures, it is believed that the negative spaces may have held some ritual significance, with the spaces between the temple columns and spaces between the figure’s arms and torso being used to hold charms, ritual weapons, or other objects. Of many Mezcala standing figure sculptures identified, the one pictured above is relatively large; given its scale, it is believed that this object was carved from an original piece of stone, rather than being reworked from an earlier celt, axe, or ritual object.

The unique styles and media used in the three Mezcala temples (above) reveal the diversity of the traditions associated with temples and sculptures representing temples in the Mezcala-Chontal culture. The Mezcala Temple at the left is similar to the two previous Mezcala temples shown in this analysis. As in both of those examples, this one is carved with horizontal slashes representing stairs at the base, four vertical columns, and a horizontal plinth bearing a recumbent figure; in this example, the figure is facing to the left, whereas in the other examples the figure is facing to the right. The Mezcala Temple with the rounded top, shown in the center above, like the other Mezcala temples in this analysis, has four vertical columns with stairs at the base, but lacks the familiar figure; the horizontal plane atop the four columns is topped with a convex semicircle. The Mezcala Temple at the above right similarly depicts a temple structure with four columns, however, it is distinguished by a more three-dimensional structure; this may represent interiors of temples or a specific architectural structure. Mezcala architectural models or temples of this period usually accompanied burials and remains of influential people, leading some scholars to believe these may have symbolized the expectations or the foundations for dwelling in peace and happiness after death.

Costa Rican/Maya Style

The Maya Half-Celt (above left) and Maya Half-Celt (above right) together hint at the connections between these objects as well as broader trade and cultural networks spanning Mesoamerica. Both of these objects are carved from a dark green jadeite stone, which likely originated in Guatemala. The stone was likely first carved into a celt during the earlier Olmec civilization, and then brought to Costa Rica through trade. These celts were rendered in their current forms during the Classic period, between 600 and 900 CE. Scholars have found that many Maya cultures recycled earlier objects, and that the use of earlier objects to fashion new objects was seen as conveying status and power. Both celts are decorated with intricate surface carvings featuring anthropomorphic figures. The deep green jadeite is associated with significant Maya spiritual and sociopolitical iconography. All of these elements together demonstrate the maintenance of beliefs around agricultural and human cycles of life, and reveal a glimpse of the often-hidden pasts of the objects themselves that stretch back to their geological and Olmec “pre-dawn lives.”

Maya

This Maya Pendant (above) is in the Nebaj style, carved during the late Classic period, a time when Maya civilization is believed to have been at a cultural, social, and economic peak. Similar to the objects above, this pendant depicts a figure representing a ruler or deity such as Itzamná—a sun, sky, and creator god. Often associated with K’inich Ahau, a Maya maize god, such pendants also are seen to demonstrate attributes of K’uk’ulkan, which translates to “plumed serpent.” A similar deity and figure in Mesoamerican culture is Quetzalcoatl, whose prominence rose in the post-Classic period in Mexica and Aztec traditions. The figure on the pendant is carved in profile, as with the figures carved in the hacha, above; the curved lines extending from the back of the head may represent anthropomorphic aspects, or quetzal feathers. This creation also shares many attributes with a related piece related to Ahau-Kin (one expression of the sun) and the Maya Jaguar god of the underworld, excavated at Teotihuacan. The visual language established in this piece calls on earlier styles, but invokes greater naturalistic detail in the rendering of the human form. Elements of this visual style persist, and can be seen, re-envisioned, and transformed further in the post-Classic era.

Part III

The Third Sun and Corresponding Archaeological Timeframe: Post-Classic ~ 900 CE–1521 CE

In works of art made in Mesoamerica during the Post-Classic era we see further evidence of the interconnectedness and relationships between Mesoamerican cultures that were contemporaries to one another. We witness these connections in the parallels in subject matter and the stylistic representation of subjects in sculpture. Works of art from this period draw on the rich artistic and cultural traditions of Mesoamerica established by the Olmec, and in the Pre-Classic and Classic eras explored above. The reappropriation of representational styles by artists in this era can be seen as having a parallel to the cycles of life, death, and rebirth that were prominent themes in the spiritual and cultural practices of the Maya and Mexica.

Maya/Mexica or Triple Alliance

The Post-Classic Maya/Aztec (Mexica) Mask of Xipe Totec (above left) represents the multi-ethnic deity whose name translates to “our lord the flayed one.” Xipe Totec was also the brother of Tezcatlipoca, Huitzilopochtli, and Quetzalcóatl. The artwork, completed circa 1300 CE, reveals many visual links stretching back to the Olmecs, and characterizes the particular ways artists of the Post-Classic era interpreted these forms. The red hue is linked to blood and fertility, as well as the reciprocal relationship between humans and the deities necessary to maintain ecological and cosmic balance—sometimes through ritual sacrifice. The earplugs here are flowers, reflecting the cycles of life, death, and rebirth. Xipe Totec was a prominent figure in both Maya and Mexica cultures. The possibility that this particular object may be associated with both the Maya and Mexica cultures reveals the deep and spiritual connections between these cultures in Mesoamerica, especially as the Triple Alliance and Maya polities expanded during the Post-Classic era.

The Aztec (Mexica)/Toltec Standing Figure of Xipe Totec (above right) displays this deity in a format that accentuates Xipe Totec’s associations with rebirth, associated with the shedding of skin as part of transformation, referencing the shedding of a snake’s skin or the removal of husks from corn. Carved from basalt, these elements are referenced in the sculptural details around the figure’s eyes and mouth: The concentric rings represent a layer of skin being donned by the figure that could be removed or shed as part of rebirth; in rituals associated with Xipe Totec, priests associated with the deity would wear the skins of sacrificed individuals. Xipe Totec was believed to the source of diseases and thus could be sought to cure human ailments. Xipe Totec is often associated with the Toltec site of Cholula, a culture revered by the Mexica and many other cultures as the height of civilization from a “pre-dawn” era; many Mesoamericans living during the Post-Classic claimed ancestry from Cholula.

Like the figure of Xipe Totec depicted above, the Aztec (Mexica) Seated Figure is carved from volcanic stone. The figure is depicted as wearing adornments that denote status: The headdress includes quetzal feathers, which were highly valued due to their association with prominent deities in the Mexica panoply. The elaborate ear adornments worn by the figure also may denote status, class, and authority; adornments such as these are associated with ritual and status in Mexica culture, and are also sometimes deemed as representations of fertility and agricultural renewal. The structures of the figure’s body and facial features stylistically connect this work with earlier representations crafted by Olmec artisans and artisans from the Pre-Classic era.

The Aztec (Mexica) Mask (above) displays the way that artisans in the Post-Classic era sought to realistically convey human features while also engaging stylistic connections to works created by earlier Mesoamerican cultures, including the Olmec, Teotihuacan, and Maya. The work likely functioned either as a face mask worn in rituals or as a death mask; the concave eye sockets may have originally been inlaid with precious metal or stone.

The depiction of serpents with feathers or features of birds—such as the Aztec (Mexica) Plumed Serpent (above)—are often identified with Quetzalcóatl, one of the most important deities in the Mexica panoply. Maya cultures in the Classic and Post-Classic era also worshipped a feathered serpent deity, known as K’uk’ulkan. Feathered serpent deities play prominent roles in many stories in Mexica and Maya cultures concerning the creation of the world. The earliest representation of figures with these anthropomorphic qualities can be found in art and artifacts from the Olmec culture. Deities such as Quetzalcóatl and K’uk’ulkan are associated with creation, fertility, rain, knowledge, and the arts.

Shown together, the Aztec (Mexica) Frog (above left) and the Aztec (Mexica) Squash or Gourd (above right) together demonstrate links between the spiritual and natural worlds in Mexica cultures in Post-Classic Mesoamerica. Both frogs and gourds are representations of fertility, and are associated with water and rain—natural resources necessary to sustain agriculture and the survival of humans, animals, and ecosystems. The Aztec squash or gourd may also represent currency and prosperity: The agricultural practices of Mesoamericans in the Classic and Post-Classic era were a fundamental part of what enabled the Maya and the Aztec to flourish.

Mixtec/Mexica or Aztec/Triple Alliance

The panoply of three of the most prominent cultures during the Post-Classic era—the Aztec, the Mixtec, and Tlaloc—includes fertility deities associated with rain. These deities—respectively, Tlaloc and Dzavui—are depicted in the works above, a mask and a standing figure. The Aztec (Mexica)/Mixtec Mask of Tlaloc (above left) and the Mixtec Standing Figure of Dzavui (Tlaloc) (above right), both carved from jadeite, demonstrate similar features—representing the cultural and stylistic links between these cultures and their practices. Both sculptures depict their subjects as wearing elaborate headdresses and ear adornments. The facial features—notably the large eyes, prominent upper lip, and open mouth—recall stylistic traditions established by Olmec and other “pre-dawn” cultures in Mesoamerica.

Casas Grandes Paquimé

The Casas Grandes or Paquimé Bowl (above left) and Casas Grandes or Paquimé Bowl with Effigy Rabbit Heads (above right) both originated in the same era as the above works, estimated as having been crafted between 900 and 1300 CE. Both objects originated in the Casas Grandes culture, which flourished in this era across a region that spanned from what is now Sonora in Mexico to southern Arizona in the United States. These polychrome pottery works are ollas, vessels that were used for cooking. Their surfaces are decorated with designs that reveal the intersection between everyday objects, cultural practices, and ritual. The vessel on the right has two rabbit heads sculpted in relief that could have been used as handles; archaeologists have found rabbit remains in Casas Grandes excavations, indicating that they were likely raised and bred for their pelts and food.

As all of the works in this analysis have indicated, there were stylistic and cultural links between many Mesoamerican cultures in the millennia preceding the colonization of North America by Europeans. The links between these works and the Casas Grandes culture and Native American cultures of the Southwestern United States blur the artificial lines between past and present indigenous societies as well as the constructed nature of contemporary borders.

Part IV

The Fourth Sun and Corresponding Archaeological Timeframe: Colonial–Contemporary Eras ~ 1521–Present

“Here, then, is the beginning of when it was decided to make man, and when what must enter into the flesh of man was sought. And the Forefathers, the Creators and Makers, who were called Tepeu and Gucumatz, said: ‘The time of dawn has come, let the work be finished, and let those who are to nourish and sustain us appear, the noble sons, the civilized vassals; let man appear, humanity, on the face of the earth.’ Thus they spoke. They assembled, came together and held council in the darkness and in the night; then they sought and discussed, and here they reflected and thought. In this way their decisions came dearly to light and they found and discovered what must enter into the flesh of man. It was just before the sun, the moon, and the stars appeared over the Creators and Makers. From Paxil, from Cayalá, as they were called, came the yellow ears of corn and the white ears of corn…….After that they began to talk about the creation and the making of our first mother and father; of yellow corn and of white corn they made their flesh; of corn-meal dough they made the arms and the legs of man. Only dough of corn meal went into the flesh of our first fathers, the four men, who were created.”

(Goetz, Delia, and Sylvanus Griswold Morley. The Book of the People = Popol Vuh: the National Book of the Ancient Quiché Maya. Printed for the Members of the Limited Editions Club at the Plantin Press, 1954. pp 48-49.)

The works shown above (left to right: Aztec (Mexica) Life-Sized Head, Mezcala-Chontal Standing Figure, Aztec (Mexica) Coiled Rattlesnake, & Mezcala/Sultepec Mask) represent works attributed to Mexica and Mezcala cultures in Central America over the span of more than 3,000 years.

In the early 1900s, modern artists from Europe, including British sculptor Henry Moore and Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, took inspiration from artworks from the pre-colonial cultures of the Americas and Africa, incorporating the geometric and stylistic forms into their works. While this demonstrates the Eurocentric appropriation of these cultures, this modern recontextualization also reveals the continued lives of these works within and beyond their immediate context in their culture and place of origin. The range of influence that early works from pre-colonial Central and North America has had in a variety of contexts challenges people to consider what makes something “modern.” The artistic influence of these early works on later works of art also challenges the assumptions people make regarding both ancient and contemporary works of art.

The influence of early Mesoamerican cultures can also be clearly seen in the work of 20th century artists who have cultural heritage ties to the pre-colonial cultures of the Americas. Mexican artists including Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo incorporated Mesoamerican narratives, forms, and ideas into their murals and works. Their reimagination of Mexico’s future following the Mexican Revolution in 1910 embraces the cultural iconography of the indige nous people of Mexico; their work has gone on to influence future generations of artists.

The painting above (Creation) is a draft illustration by Rivera for an illustrated manuscript of the Popol Vuh by John Weatherwax that was never published. The illustration depicts two serpentine deities creating the world; these representations may be considered in parallel with the Aztec (Mexica) Coiled Rattlesnake and the Aztec (Mexica) Plumed Serpent.

The illustrations for Diego Rivera’s Popol Vuh also incorporate representations of deities associated with the Mayan Hacha likely representing those interpreted by Mayan and Mixtec artists in the Mayan Hacha of God Head with Human Face (which is interpreted as a representation of Chaac or Tlaloc) (above left), and Mixtec Standing Figure of Dzavui (Tlaloc) (above right). These works and others like them add to a legacy of work from Mesoamerica that inspires artists to imagine possibilities of liberation from colonization, and to reclaim and celebrate the art and culture of their pre-colonial Mesoamerican ancestors.

Mexican painter Frida Kahlo collected pre-colonial works of art from Mexico. Sculptures representing figures, similar to the Colima Standing Figure (above right) are depicted in several of her works, including her 1938 painting Four Inhabitants of Mexico. Kahlo’s interest in the culture and artistry of the indigenous people and cultures of Mexico served to drive greater interest in pre-colonial artworks from Mesoamerica among both art historians and the greater public.

The mural Toltecas en Aztlan by Guillermo Aranda, Arturo Roman, Salvador Barrajas, Jose Cervantes, Sammy Llamas, Bebe Llamas, Victor Ochoa, Ernest Paul, Guillermo Rosete, Guilbert “Magu” Lujan & M.E.Ch.A. group from UC Irvine (above at top), renovated in 1988 features a depiction of what appears to be a large stone sculpture depicting a head in the Olmec style at the center. The stylistic link between this work and the Olmec Mask and the Olmec Mask Fragment from the Vilcek Collection shown above are evident, despite being separated by thousands of years, and being produced in different mediums, and for different purposes.

Contemporary artists of the Americas continue to draw on the inspiration of their 20th century forebears including Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and José Clemente Orozco in connecting with the cultures of pre-colonial Mexico and crafting new representations of mythical figures and deities that are first recorded in pre-colonial artworks.

Borders and boundaries between communities and nations have shifted over time, as a result of geography, imperialism, colonization, and forced segregation. Art and the creative impulse are universal to the human experience and transcend these borders and boundaries. As we examine the influence of pre-colonial artworks from Mesoamerica, we see, too, how their forms, traditions, and materials also transcend time, spanning millennia.

Communities throughout the Americas are grappling with the way that imperialism and colonization led to the genocide of indigenous people and communities, leading to the loss and erasure of historic and cultural knowledge. Many contemporary artistic movements have been inspired by 20th century artists including Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo to explore the pre-colonial art, history, cultures, and traditions of these regions, and to take inspiration from them in their work.

Examples include muralists like those who created Toltecas en Aztlan, and the dozens of others that adorn the walls and structures of Chicano Park. Chicano Park is a National Landmark in Logan Heights, a Mexican American neighborhood in San Diego, California. The neighborhood and park have become a center of cultural activities for persons with heritage in the territories of Mexico and the United States in the pre-colonial era. Some of the murals in Chicano Park also acknowledge that the border wall marking the current boundaries of the United States and Mexico bisects and disrupts the ancestral land of the Kumeyaay nation.

The work of contemporary artists such as Connie Perez and the muralists whose work is displayed at Chicano Park represent the ongoing influence of pre-colonial cultures and their artwork. Together these examples and all of the creations highlighted here help the viewer to imagine new possibilities, reminding us that the links between the past, present, and future are complex, and that we all have abilities to shape our futures, which also bind us to the dreams and aspirations of all generations.

Related News

You may also be interested in

Aztec (Mexica) Plumed Serpent

Aztec (Mexica) Seated Figure

Aztec (Mexica) Life-Sized Head