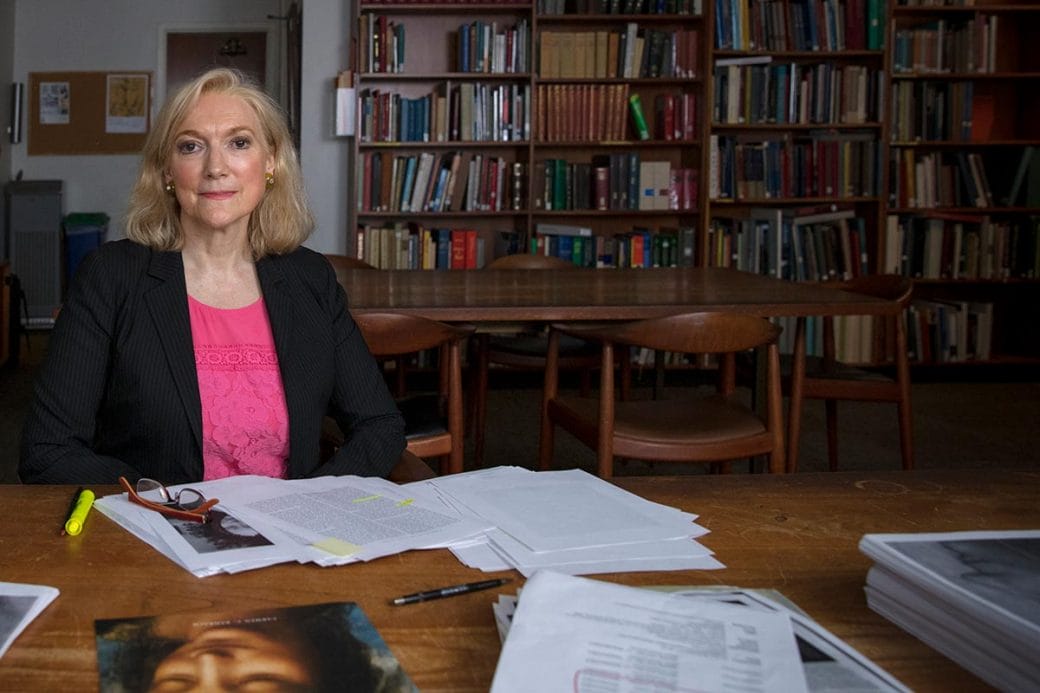

Chilean-born art historian and curator Carmen C. Bambach is the recipient of the inaugural Vilcek Prize for Excellence. Created to honor immigrants who have had a profound impact on American society and world culture, she is an appropriate standard-bearer: Throughout her career, Carmen’s expertise in Renaissance art has reshaped how we understand works created half a millennium ago, while making it more accessible to the general public today.

Her passion for Renaissance art goes back to childhood. As a young aspiring artist, Carmen would immerse herself in books on the topic, taken by its technical virtuosity, expressive power, and vivid portrayal of both anatomical details and psychological nuances.

“It was like a magnet for me,” Carmen says. “I would sit for hours and copy the Delphic Sibyl or the Prophet Jonah from [books on] the Sistine Chapel.”

At age 14, Carmen immigrated with her family to escape the political upheaval of 1970s Chile. They settled in Connecticut, which seemed to them to have “a very exotic culture.” Although the adjustment wasn’t easy, she wasted no time learning English and taking advantage of the educational opportunities offered by the move; it was, Carmen says, “the greatest gift my parents have given me.”

Her enthusiasm for learning continued through her undergraduate studies at Yale University, where she majored in architecture and art history. While conducting research for her senior thesis on the Sistine Chapel, Carmen discovered a drawing by Michelangelo, created in preparation for the Sistine Chapel, that had been labeled as an armpit.

Carmen, however, turned the drawing upside-down and recognized it as a study for the optical effects Michelangelo used to portray human figures on an outsized scale. “I had been drawing Jonah in the Sistine Chapel with a foreshortened head since I was 12 years old,” she says. “That gave me the ability to recognize that it is really a fragment of the foreshortened face.”

At that time, the Sistine Chapel was undertaking a 15-year restoration, and with support from her advisors, as well as Fabrizio Mancinelli, the Vatican official overseeing the restoration, Carmen was able to visit the Sistine Chapel to investigate her hypothesis. “I climbed on the scaffolding, held up the transparency, and it fit perfectly on the face of Haman,” Carmen says.

The discovery was revolutionary, and laid the foundations for a career that would change the way scholars understood the usage of drawings in the complex technical process of creating panel paintings and frescoes during that period.

At the time, however, it also brought to light the disparate ways that Carmen’s work would be received as a young Latina immigrant in a male-dominated field. “Professors usually had two reactions,” she says. “One is, ‘Who are you? What do you think you’ve discovered?’ And the other would be professors who [were able] to embrace a different way of thinking.”

Carmen persevered in the face of such resistance. Her parents had taken great risks to move the family abroad, and in the years prior to Pinochet’s revolution, they had witnessed the frightening rise of a dictatorship that severely curtailed many freedoms, including freedom of speech.

She honored that risk, then, by honing a sense of intellectual courage. “Thinking outside the box is something that happens when you know that you don’t really fit in culturally,” Carmen says. “So I embraced my own weirdness, and it gave me an incredible sense of comfort. It gave [me] permission to be stubborn.”

In the years since, Carmen has been rewarded for that courage. With the support of the Yale academic community, she continued studying the role of drawings in the creation of Renaissance art, completing both a master’s degree and PhD in art history there. She published the results of her research as a textbook, Drawing and Painting in the Italian Renaissance Workshop (1999), which is now required reading for students of Renaissance art, and she has authored over 70 scholarly articles and several exhibition catalogues.

After earning her PhD, Carmen taught art history at Fordham University before joining the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a curator of Italian and Spanish drawings in 1995. There, she organized exhibitions on many Renaissance masters, including Bronzino, Correggio, Filippino Lippi, Parmigianino, and Raphael.

The exhibitions she is most proud of, however, are Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer (2017–18), and Leonardo da Vinci: Master Draftsman (2003). They incorporate two goals that are important to her as a curator: examining art as the products of a specific personality and set of social circumstances, and making art more accessible to a wider public audience. Michelangelo, widely lauded as a blockbuster exhibition, is a stunning achievement of the latter. Curated to demonstrate the foundational role of drawing in the maestro’s work in a variety of media, the exhibition included 133 of Michelangelo’s drawings, shown alongside works in marble, an architectural model, and a painting.

Drawings, due to their delicate nature, are rarely lent—and even more rarely travel abroad. “Asking for each drawing was like asking for the heir to the throne,” Carmen says. She worked on the exhibition for a decade, traveling extensively to arrange the loans, and the result was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, as most of the drawings will not be exhibited again for many years.

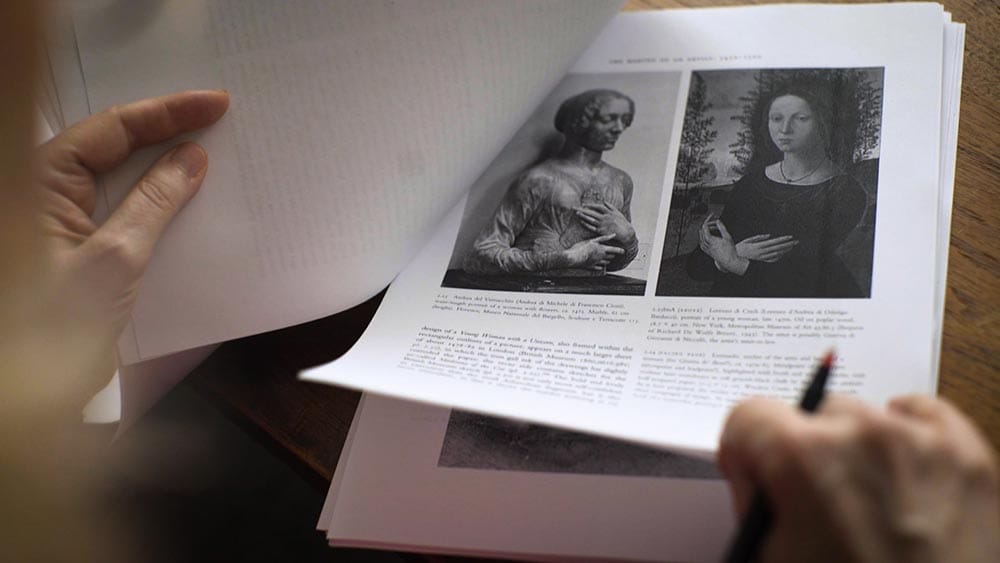

The 2003 exhibition on Leonardo da Vinci—“My other love,” Carmen calls him—provided a portrait of the artist through his drawings, preparatory sketches, scientific notations, and presentation drawings of his masterpieces. It also highlighted the various biographical influences that impacted da Vinci’s work, such as being self-taught, left-handed, and born to unwed parents.

The research for that exhibition formed the basis for Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered, Carmen’s four-volume monograph that will be published through Yale University Press this summer. Commemorating the 500th anniversary of his death, the monograph is a modern rethinking of the career and vision of da Vinci, the result of a painstaking study of over 4,000 sheets of notes and 1,500 drawings that has uncovered new narratives and insights about his life.

“I’ve been dedicated to writing this book since 1995,” Carmen says. “It feels like a child who has gone to college and grad school.” It is indicative of the meticulous yet original scholarship that has earned Carmen numerous honors, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and membership in the American Academy of Arts and Science and the Villa I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance.

But most of all, it is exemplary of the way that Carmen has single-handedly revolutionized a field of study, proving that intellectual courage—combined with a touch of weirdness—can turn centuries of accepted thought on its head.

Related News

Celebrating Independence: Great Immigrants, Great Americans

Vilcek Foundation Awards $250,000 in Prizes to Immigrant Curators

Oluremi C. Onabanjo: Expanding the Horizons of Photographic Histories

You may also be interested in

Carmen C. Bambach

Oluremi C. Onabanjo

Francesca Du Brock