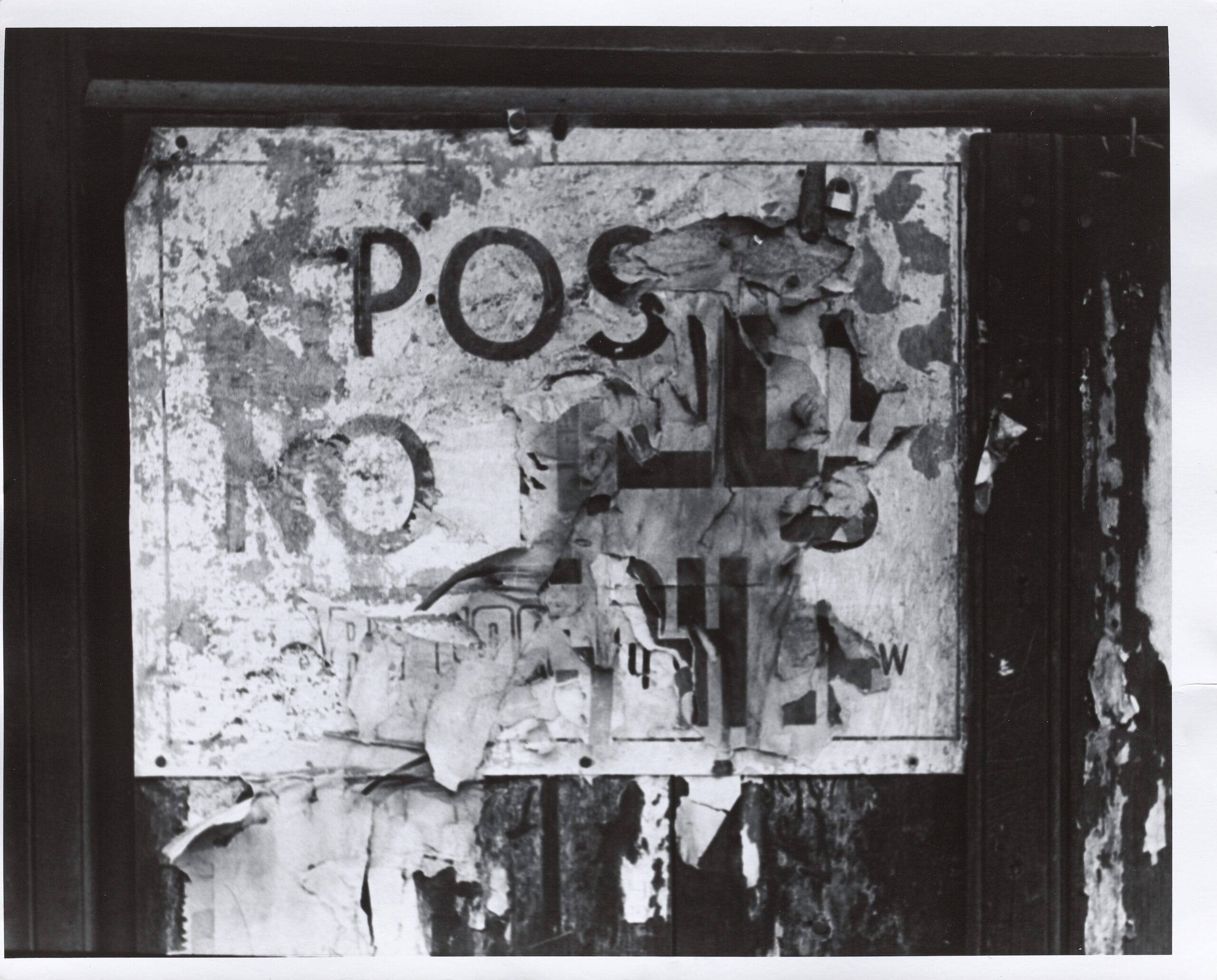

Crawford began experimenting with photography in 1934, but his breakthrough in the medium came in 1938, the year he created Torn Signs, Philadelphia, an image of a ripped and pasted-over “Post No Bills” sign. The simultaneous buildup and decay of weathered advertisements papered across cities from New York to Pamplona, Spain, spoke to Crawford. He returned frequently to the motif in the last 30 years of his life, creating an incredible body of work that became his longest-running series: There are at least 70 photographs, drawings, and paintings that relate to the Torn Signs theme.

Crawford’s last series, begun in the early 1970s, centered around images of Semana Santa (Holy Week) in Seville, Spain. Semana Santa, the week that precedes Easter in Christianity, is observed with public processions of penitential confraternities and pasos (floats) through the city streets. Crawford first traveled to Spain in the 1930s, visiting Mallorca and possibly Seville. He returned to Seville after the war, making at least five trips in the 1950s and ’60s, although the exact dates of some of these trips have yet to be pinpointed. In the early 1970s, Crawford documented three trips to Seville for Holy Week, and the images he recorded on film and paper became the basis for paintings, etchings, and drawings. For Crawford, the rhythmic images of hooded penitents processing through the streets recalled formal elements of his Torn Signs imagery.

The confluence of Torn Signs and Semana Santa, two seemingly disparate themes, reveals Crawford’s extraordinary visual memory, working method, and inventiveness. Over the course of nearly four decades — from Torn Signs, Philadelphia, 1938, to Santa Semana, 1976 — he drew inspiration from a constellation of memory and invention, recording and transforming his experiences. The convergence of these two incredible series culminated in the powerful, large-scale painting Torn Signs, April 15, 1974-76.

Torn Signs and Semana Santa

This group of eight works reveals the crosscurrents that flow through both the Torn Signs and Semana Santa series, and illuminates the depth of Crawford’s visual memory. In this set, over the course of 20 years, Crawford revisited and reconsidered the connections between the two series. From a lithograph to four photographs, an oil painting, a drawing, and a watercolor, we see Crawford’s mastery of five different media on full display.

Beginning with a lithograph, this group offers the opportunity to examine Crawford’s process, which, as he made clear through precise dating, was neither a chronological progression nor the default process we often think of, from photograph to drawing to finished painting. Seville, 1957, contains several elements that suggest a connection to both the Torn Signs and Semana Santa series. On the left-hand side, the tan rectangle marked by seven horizontal black lines is reminiscent of a sign with extensive lettering. While on the right, a conical black form echoed by a flipped black cone foreshadow the hooded penitents in Crawford’s 1972 photographs of Holy Week and his late paintings of Seville.

Three photographs of ripped posters, featuring a man who has been literally defaced, were each printed from a different negative (24, 26, and 30) on the same roll of film. Fragments of text appear in only one photograph, frame 26, and reveal no clues about time or place. The composition of this photograph becomes the basis for Torn Signs, the largest painting in Crawford’s oeuvre.

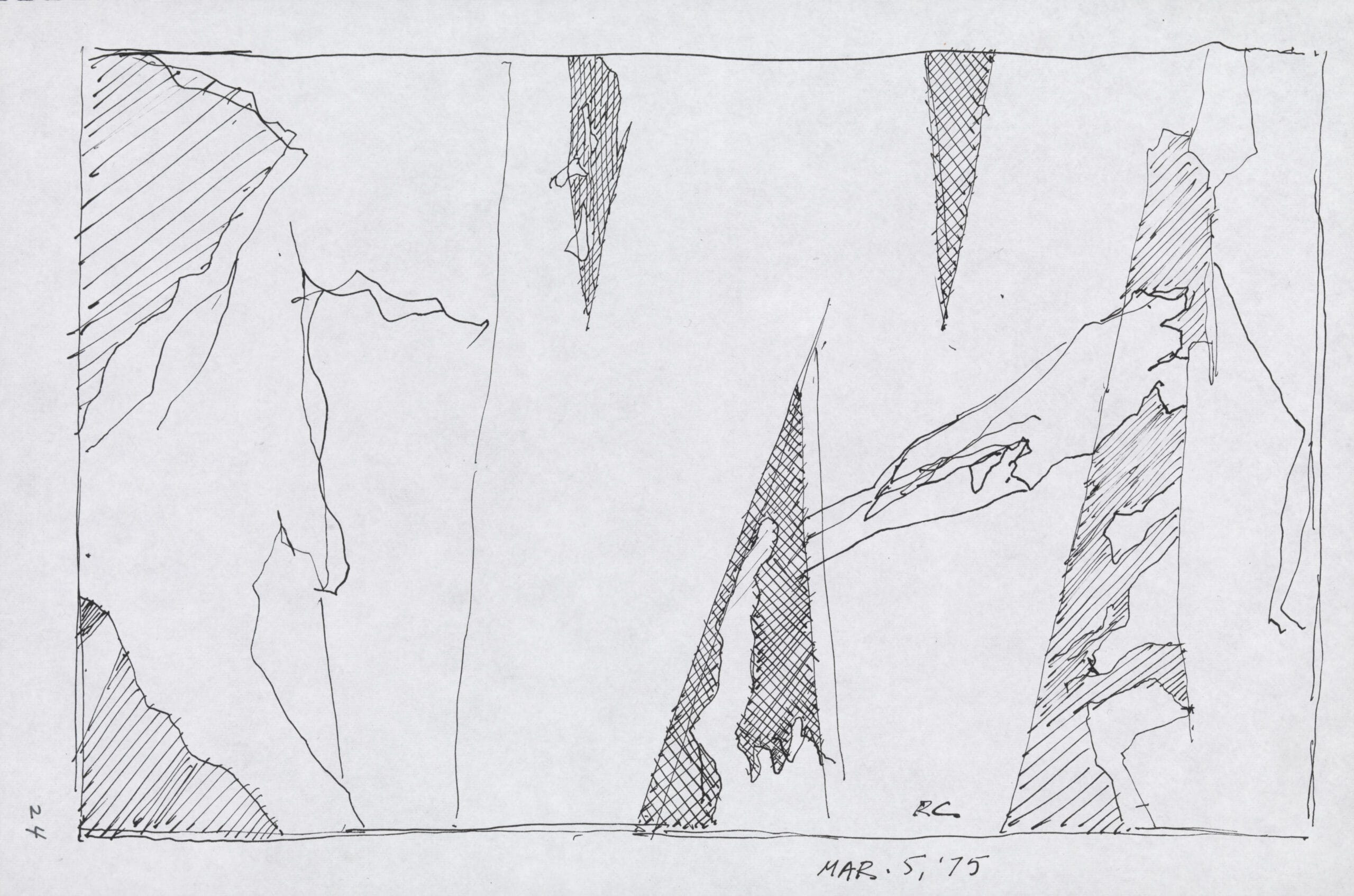

According to the inscription on the stretcher, Crawford began the painting on April 15, 1974. It was not unusual for Crawford to date works exactly, but it was a practice he generally reserved for drawings. This suggests a significant connection between the date he started the painting and the painting itself. April 15, 1974, was the Monday following Easter Sunday, a date that must have drawn Crawford’s thoughts back to Seville. In the painting, the torn edges of poster text are transformed into the hoods of penitents, which we see processing through the streets in Santa Semana, 1972. The related drawing was created almost a year later, on March 5, 1975; it is not a preparatory sketch, as one might first assume.

In the drawing, Crawford focused in on the photograph, tightening the composition and sharpening the lines. A year after the painting’s completion in 1976, he returned to the composition, creating a watercolor entitled Los Penitentes at the Cathedral, 1977. Its palette of pinks and blues relate to the colors in Signs, 1973–76, illustrating the constellation of connections between Torn Signs and Semana Santa.

Semana Santa Penitents

During his 1972 trip to Seville, Crawford photographed the penitents taking part in the Semana Santa processions. These images capture the emotion of the event and immerse the viewer in the scene. It was a moving experience that resonated intensely with Crawford, and he revisited the theme in the weeks immediately following his trip as in After Seville, May 8, 1972, and then for years after. Crawford reimagined it fresh on each occasion, emphasizing different aspects of the event, while retaining the excitement of the initial experience.

A couple of the photographs convey the larger scene, but most focus on the procession, placing the viewer at times in the role of spectator, jostling with the crowd. At other times, the viewer is thrust so close to the penitents as to feel like a part of the procession. It is rare in Crawford’s oeuvre to find a one-to-one connection of photograph to drawing or painting, and this series is no exception. All of the works relate in theme, and while the compositions often draw on elements that echo one another, every work is an invention, a combination of experience and emotion.

In Blue, Grey, Black, 1973, a group of hooded penitents are reduced to flat planes of color. The crowd has been eliminated along with any details that reveal the subject of the painting: If we did not know it, we may not be able to guess just by looking. While the title does not shed much light on the subject, it reveals a fascinating aspect of Crawford’s working method. The painting has an almost identical title and shares its palette with a lithograph of broken glass created 16 years earlier. As the artist’s son, John Crawford, has pointed out, his father used titles to illustrate further the “collage effect of his approach, which we see in subject matter, formal elements, and palettes.”

Constellations of Color

Excerpts from a sketchbook from 1971 illuminate Crawford’s incredible visual memory and his approach to remembering color through writing. Drawings of Semana Santa and torn signs are interspersed with sketches of the streets of Seville. The pages reveal some of Crawford’s thoughts on color and the connection between drawing and writing. The related palettes of Las Tres Estrellas, 1973, and Signs, 1973–76, further illustrate Crawford’s visual memory, the role of color, and the expansive constellation of connections between the Torn Signs and Semana Santa series.

The “pinkish violet” in both paintings calls to mind Crawford’s descriptions of the colors south of Tarbert, a village on the Isle of Harris in Scotland. On several pages in one of his sketchbooks, reproduced here and on view in this space, he wrote of the “pinkish violet” of the heather, which was “in (almost) full bloom,” and the Scottish thistles with its blossoms “also of a pinkish violet hue.” Further references to “peat black,” “green grass,” and the “near cobalt blue of the lochs and the sea” correspond to the palette of Signs. The “cool grey” of the rocks appears in Signs, and Torn Signs, April 15, 1974–76, while the “tints of yellow oc[h]re” recall the tip of the hood in Blue, Grey, Black and the shocks of color in Torn Signs.

This virtual exhibition is a condensed version of Ralston Crawford: Torn Signs, which was on view at the Vilcek Foundation from May 15-November 13, 2019.

You may also be interested in

Dayton Art Institute opens “Ralston Crawford: Air + Space + War”

Ralston Crawford: Torn Signs

Il Lee—Energy and Flow: Abstraction of Movements