When Vilcek Prizewinner Teddy Cruz first emigrated from Guatemala, he had no idea that San Diego was a border town. He did not speak English, and his relatives had warned him that going downtown would be risky and dangerous.

“It took me almost a year to exit this Truman Show,” he says. He was surprised to realize that not twenty minutes away from his new home were vibrant immigrant neighborhoods along the U.S.-Mexico border, and, just on the other side of the wall, the city of Tijuana.

It was a sharp contrast to the staid, homogenous suburbs he was living in, and Teddy began to cross the border often to spend time in Tijuana. “The texture, the ruggedness, of a place like Tijuana reminded me of my own country,” he says. “I think that oscillation back and forth between these very different ways of constructing cities [is] where my sensibilities began…as an architect.”

That realization, however, would come years later. Teddy had immigrated in the middle of his undergraduate studies as the violence of the Guatemalan Civil War worsened. It was the site of incredible inequality, and the consequences for civilians who opposed the government were severe. “People were killed in front of my eyes,” Teddy says. “Many of my friends disappeared.”

When he resumed his studies in the U.S., first at California State Polytechnic University, San Luis Obispo, and then at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, he tried to process the conflict and injustice he had witnessed as a youth. Although he had not been politically active while he was there—“I was too much of a good student”—Teddy sought to understand the ideas that had inspired such struggle, reading widely on Marxism, women’s theory, and other political philosophies.

While he had access to such teachings, however, Teddy noticed that it was not a part of his architectural studies. There was a noticeable gap between architecture as it was taught in universities and institutions, and the issues and urban conflicts that transformed living cities, such as poverty, inequality, and immigration. He grew dissatisfied with the insularity of the field, as social problems were left in the hands of developers and politicians to solve, not architects. “It was a moment of angst,” he says.

Where others might have seen a dead end, Teddy saw, simply, that the solution was to build protocols and relationships, just as one would build physical structures. He decided he did not want to open a standard commercial practice taking on upscale, design-centric projects—“architecture with a capital A,” as he calls it—and, upon his return to San Diego, he connected with Casa Familiar, a nonprofit organization serving the immigrant neighborhood of San Ysidro, which was also in the midst of rethinking how it could best serve its population.

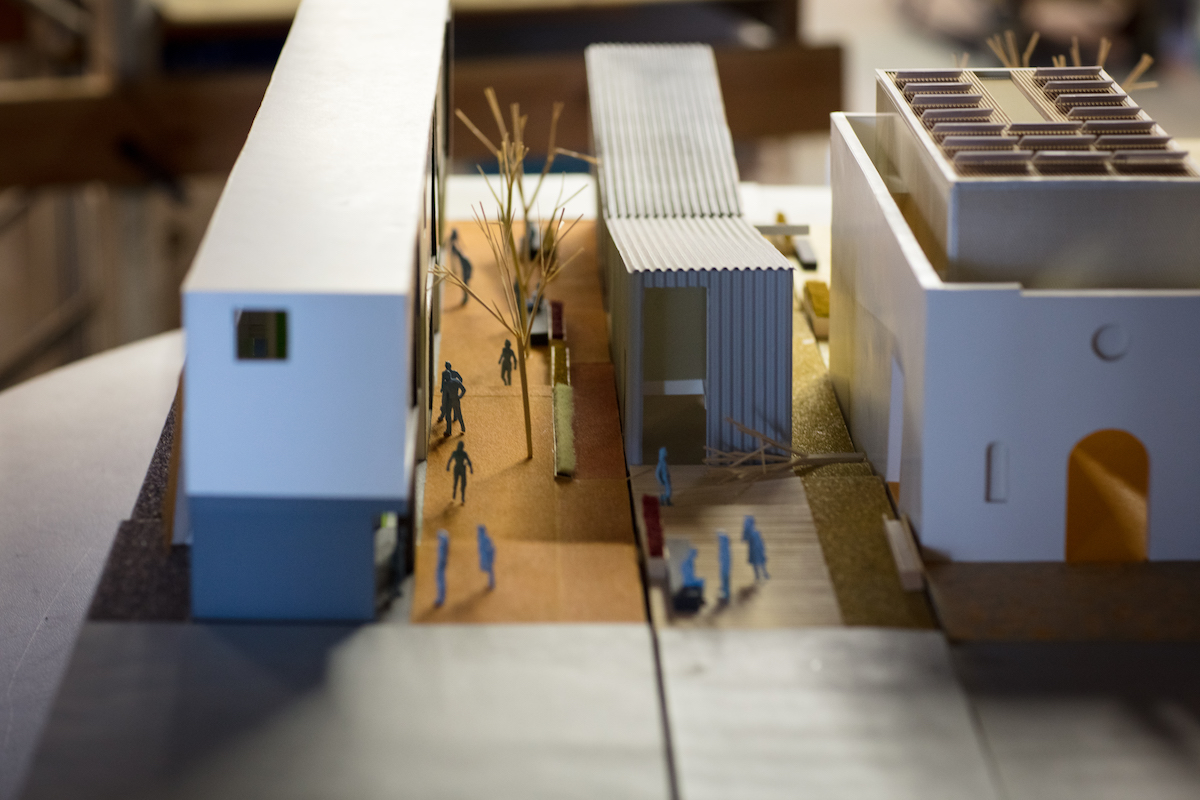

The result was an award-winning design for a 12-unit housing development, with modular structures to accommodate extended families, senior housing, and childcare services that took into account Latino cultural preferences and strove to increase both independence and community among residents. Unlike traditional architects, who design structures based on preexisting project requirements, Teddy’s involvement included working with community members to understand their needs and campaigning for zoning permits that allowed for mixed-use properties, granting greater financial independence and utility for the residents.

It would become a template for the kind of work he is known for now, as a professor of public culture and urbanism at the University of California, San Diego, and, along with his longtime collaborator and life partner Fonna Forman, the co-director of its Cross-Border Initiative and co-founder of Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman.

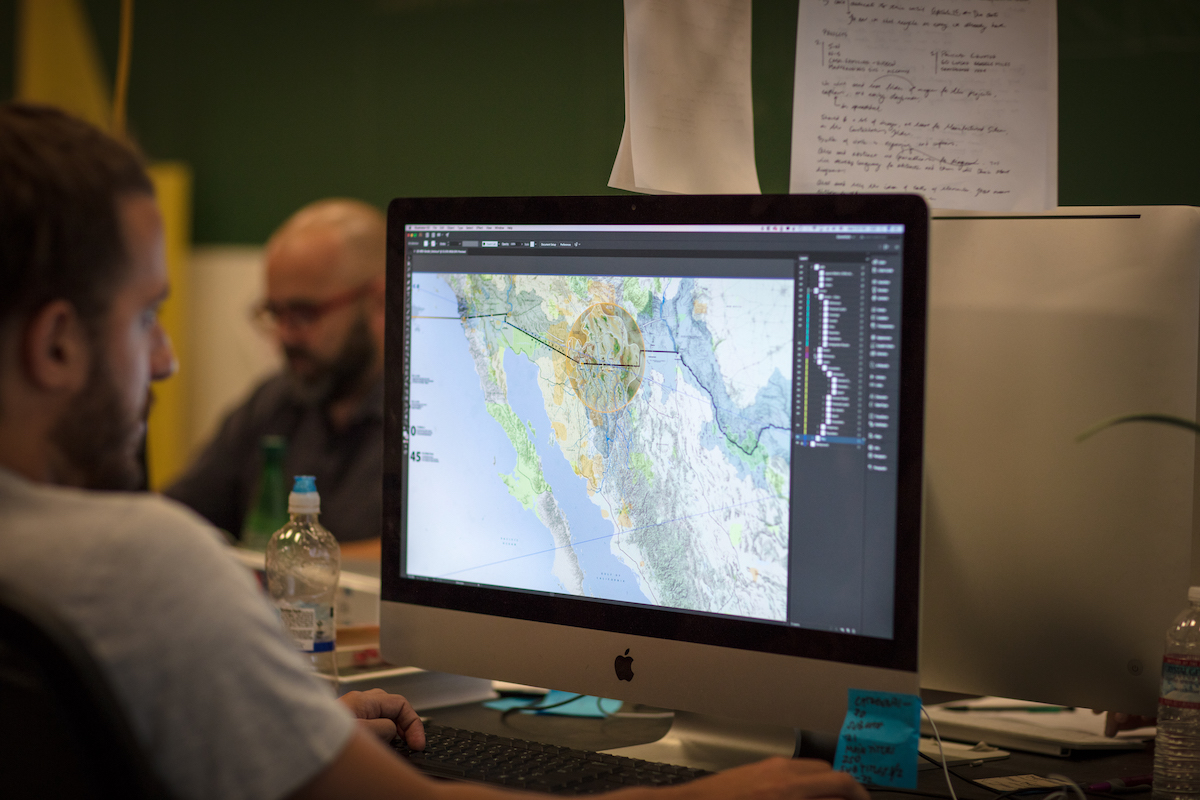

Now, he and Fonna, a political theorist, are in the process of designing other cross-border stations—community spaces along both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border that facilitate research and provide arts programming to residents. The projects aim to bring together diverse populations in San Diego and Tijuana; by considering the region as a cohesive whole, Teddy and Fonna hope to highlight the shared populations, languages, and ecologies of both cities, and to find ways to unify them. “Even though their citizens are divided right now,” Teddy says, “their destinies are intertwined.”

Created through long-term partnerships between UCSD, nonprofit organizations, community activists, and residents, the community stations are also important tools for rethinking ways that existing institutions, such as governments, universities, and architects, can confront and address pressing issues. “The Tijuana-San Diego border is an incredible laboratory, where hemispheres collide,” Teddy says. It is the largest binational metropolitan region in the world, with the busiest border traffic recorded.

Within feet of the border checkpoint is the confluence and manifestation of several issues: immigration, inequality, militarization, surveillance, and pollution. Through studying these issues, Teddy and Fonna hope to create new protocols and frameworks for addressing them in an inclusive and multifaceted manner.

Partly, this means giving voice to what Teddy calls the “creative intelligence” of immigrant communities. Many such communities have found solutions to issues of sustainability and economic marginalization through informal arrangements: for example, constructing additional living units in a single-family home to accommodate extended family, or using alleyways as farmers markets. Although these solutions have been proven to work, they are largely disregarded by policy makers, urban planners, and other institutions of power and change. “We see ourselves…as facilitators of knowledge transference,” Teddy says. “A new interface between top-down resources and bottom-up creative intelligence.”

Ultimately, Teddy believes that immigrant communities contain the seeds of societal change. Their struggles and aspirations give rise to creative strategies of survival, and their vision of the American dream is one of democratized access, inclusion, and empathy, an antidote to the toxicity of xenophobia and nationalism.

“To immigrants, the world is home,” Teddy says. Which is perhaps to say, immigrants understand that the world does not stop for a border.