Meleko Mokgosi, from Botswana, was in high school when he first realized painting’s potential for political commentary. The 2017 Creative Promise Prizewinner was then in his third year, at a time when students in his high school in Gaborone are required to select their future paths of study. Meleko had been hedging his bets, studying physics, calculus, and chemistry, along with art, but once an art teacher exposed him to German expressionist painters of the Weimar era—Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz—he was committed to becoming a painter. “It was kind of romantic,” he remembers. “I thought, I’m going to change the world by saying these things.”

After completing high school and A-levels, Meleko came to the United States to attend Williams College; upon graduation, he was accepted into the Whitney Independent Study Program, an immersive program and theory-driven for emerging artists, and later went on to study with Mary Kelly and completed a Master of Fine Arts at UCLA.

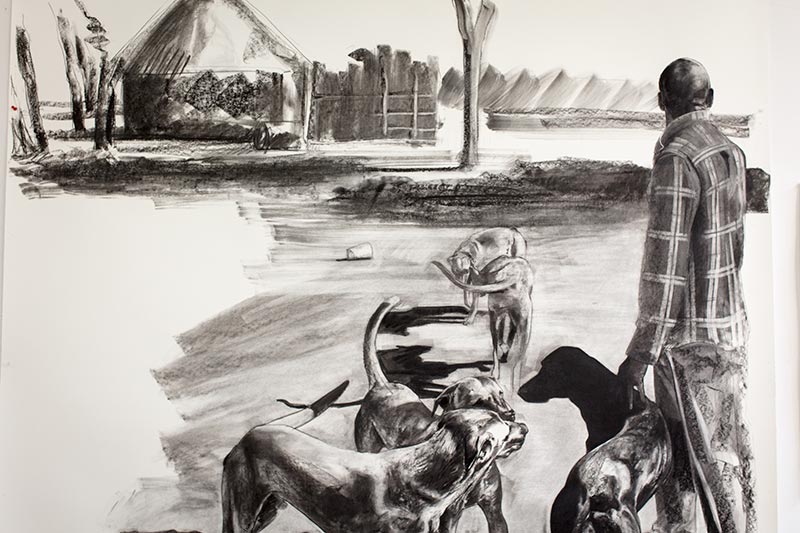

Since then, he has produced many paintings—often in titled series—that attempt to portray the complex social and political realities of Africa, and to address issues such as nationalism, anticolonialism, and xenophobia. In his installation Africanis (2013), for example, Meleko depicted various breeds of dogs found in Africa, such as the Rhodesian ridgeback, bred by colonists who saw them as an ideal mix of European and African hunting dogs, and the installation’s namesake, an indigenous southern African breed that, long disdained by European settlers, has come to be prized as a symbol of purity and “nativeness.” His installations Pax Afrikaner (2008–2011) and Pax Kaffraria (2010–2014) explore, through several paintings in each series, his experience with and observation of the xenophobic attacks in southern Africa—especially in Botswana, South Africa, and Zimbabwe—from 2007 to 2009, as well as his conviction that societies are becoming more, not less, nationalistic.

Although Meleko’s body of work are heavily charged, he no longer thinks that art will save humanity—at least not on its own. “Now, I know that you, as an artist, can’t change the world by only making art,” he says, “but you can communicate things you care about, and pose questions that you care about, and hope that something can happen after that.” So it’s no excuse to slack off—for Meleko, being an artist is a job. He arrives in his studio at 8:30 or 9 a.m., and he works for 12 hours. “I never romanticize being an artist,” he says. “Some people do. They conflate the stereotype of the “genius” artist, with muses and epiphanies, with the dream for fame and a bourgeois lifestyle. Being an artist is a full-time job like any other job out there. You search for what you want to say, how you want to contribute to the field, make your argument and call it a day.”

This strict discipline applies to the creation of his work as much as it does to its execution in the studio: Meleko usually starts by developing a title, which gives his work a conceptual framework to build upon. Then comes hours of reading and research, with Meleko diving into everything from volumes by political theorists such as Gayatri Spivak and Axel Honneth to the boxes of daily newspapers his family in Botswana saves for him to peruse whenever he returns for a visit.

Afterwards, Meleko starts making drawings for the series in mind, until he has zeroed in on a final set that will serve as a “storyboard” for the final set of paintings. The process is meticulous and thorough, and only once it is completed does Meleko finally put paintbrush to canvas. “By the time I’m painting, it’s probably been like a year and a half,” he says.

The slow, considered pace belies, however, the urgency with which Meleko works: He’s aware that to produce art about Africa is to challenge an already established narrative that has been formed, often with gross inaccuracies, through a Western lens. but not autobiographical,” Meleko says, and “deals with histories that cannot speak for themselves. There’s no time for epiphanies.”