Jing Wang, a Chinese-born musician and composer, was the recipient of a Vilcek Foundation-sponsored residency at the MacDowell Colony.

Jing Wang, a Chinese-born musician and composer, was the recipient of a Vilcek Foundation-sponsored residency at the MacDowell Colony.

“The older generation in China still considers the erhu the sound of the native land,” says Chinese-born composer and musician Jing Wang — while in the U.S., the erhu is “a symbolic representation of Chinese music.” However, thanks to Jing, an innovator in the electroacoustic field, the folk instrument is getting a remake with her smart and original compositions that mix tradition with modern electronic sound.

Jing’s love for music started at home: She recalls being 5 years old and her mother singing over a small pump reed organ played by her father. “Their passion for music penetrated into our daily lives,” she says. Her childhood home was an informal classroom, and the many fieldtrips with her father to attend concerts and ballet performances (sometimes by way of two-hour- long bike rides) certainly influenced Jing as an artist. In fact, she says, it was her father’s zeal for music that ultimately led her to focus on the erhu.

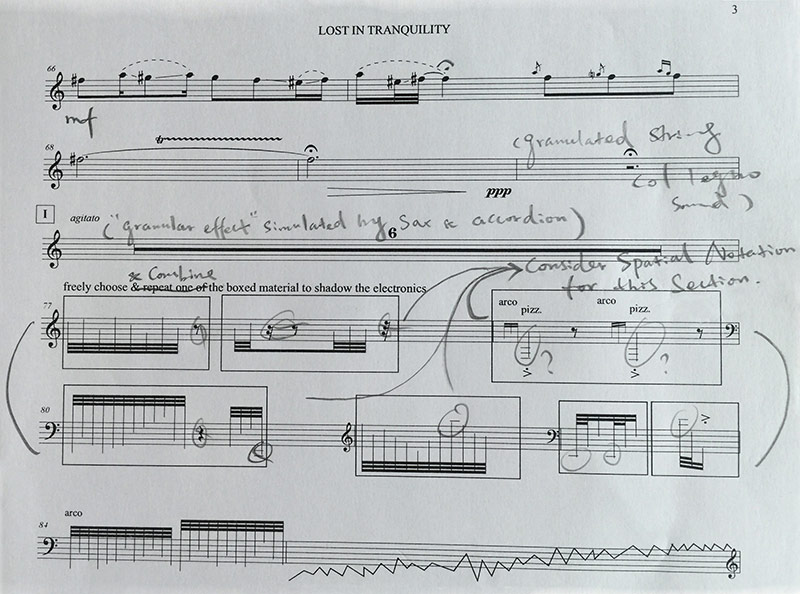

A work in progress – Jing edits the score for “Passaddhi.”

A work in progress – Jing edits the score for “Passaddhi.”

Having experimented with other instruments like the violin and piano, Jing confesses that she was initially “never completely satisfied or enthusiastic about a career as an erhu performer.” At the time, it had a limited repertoire, and Jing felt that would have restricted her performance range. However, Jing’s innovations as a composer have greatly stretched the erhu’s potential, and, indeed, sparked new interest in the instrument. Since arriving in the United States in 2000, she’s noticed a significant increase in invitations for erhu performances, workshops, and lectures.

The artist considers her immigrant experience in the United States a contributing component of her evolving artistic vision. She credits America’s creative freedom and growing global perspective as catalysts for the expression of her musical ideas and the shaping of her artistic identity. However, she is aware of the dangers, too, that immigration could pose for a budding artist: “[It] could result in negativity if one feels lost in society’s complex multiplicity of contemporary life and multicultural environment. If uniqueness and originality are important criteria by which to evaluate an artist’s work, it becomes critical for a young immigrant to comprehend one’s own culture and traditions, employing and infusing into them his or her personal artistic style.”

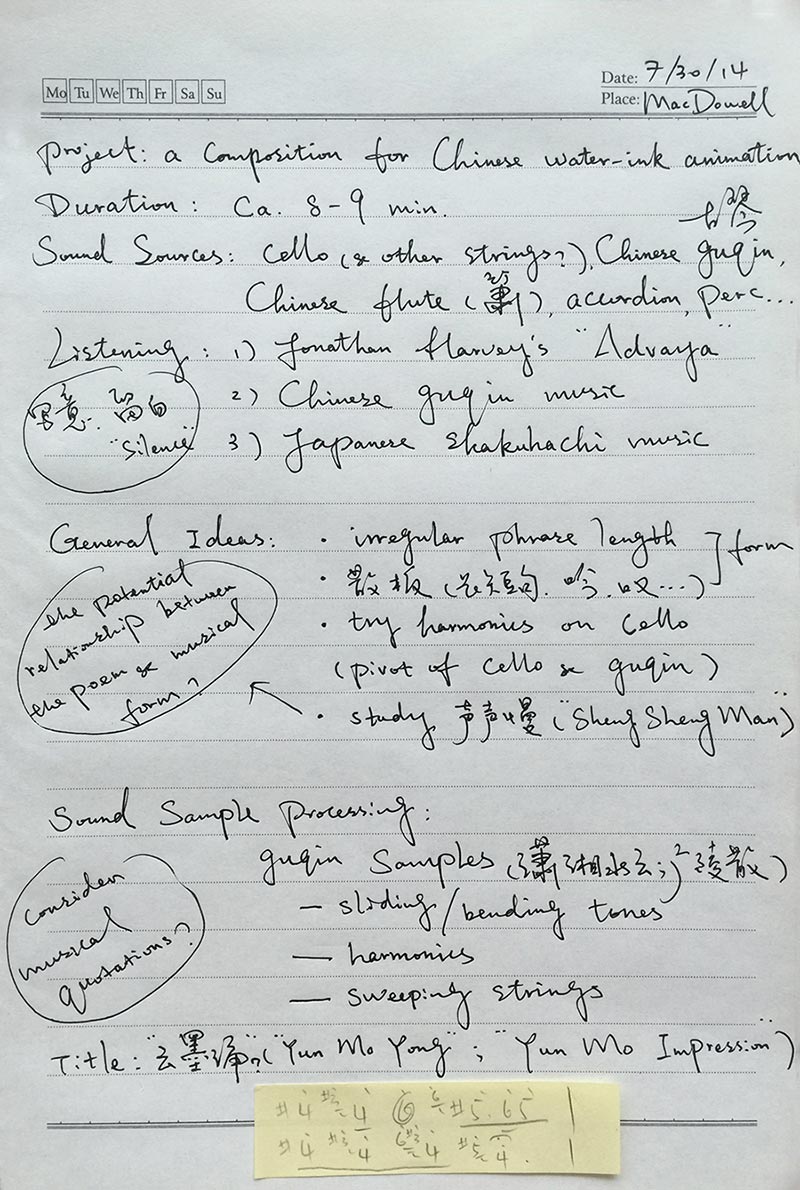

A behind-the-scenes look at Jing’s composition log, from her stay at the MacDowell Colony.

A behind-the-scenes look at Jing’s composition log, from her stay at the MacDowell Colony.

These days, though, Jing considers herself a “world citizen” when it comes to music. She’s not limited by geographic boundaries, and is passionately inspired by the possibility of dissolving divisions in music. She has introduced the erhu into a variety of Western musical contexts, from compositions for chamber ensembles to avant-garde jazz improvisations, and multicultural ensembles, and she is fascinated by a variety of Eastern folk music elements, including Peking Opera, Indonesian Gamelan, and even the techniques of Chinese water-ink painting.

Jing defines composition as “a time art, for it archives a composer’s thoughts, as well as a creative process, in very specific degrees of time and space.” She’s even created a ritual of keeping a detailed log of the development of her compositions, with goals set for each day: “It serves as the guiding force of my creative process.”

Also important to her process is the role of serendipity. “Experimenting has become a vital component in creating innovative sounds and stimulating artistic ideas, with unexpected occurrences often influencing the positive development of compositions.”

“Passaddhi”, a multimedia composition with electroacoustic sounds by Jing Wang and animation by Harvey Goldman.

“Passaddhi”, a multimedia composition with electroacoustic sounds by Jing Wang and animation by Harvey Goldman.

In 2014, Jing was honored with a fellowship at the MacDowell Colony. The Vilcek Foundation partially funded a residency for a foreign-born artist, which Jing used to experiment and compose at the colony’s grounds in New Hampshire. She describes the environment as “a naturally tranquil world, one forgotten by time.” When composing at the colony, Jing’s goal was to explore the dialectical relationship between acoustic and electronic, as well as convergence and divergence, which were analogous to the tranquility and disturbance of the colony’s environment. What resulted was “Passaddhi”, a multimedia composition that includes electroacoustic sounds by Jing and animation by Harvey Goldman, a retired chancellor professor at University of Massachusetts Dartmouth (UMD).

As an assistant professor at the College of Visual and Performing Arts of UMD, Jing Wang’s creative expression and artistic philosophies flourish: “My artistic philosophy of East-West synthesis and acoustic-electronic integration has been further developed during my teaching years there.”

Indeed, Jing has shown that tradition and innovation are not mutually exclusive; they can, and do, work together in Jing’s compositions. Jing will continue to teach at UMass Dartmouth, create and collaborate on multimedia compositions and perform her works around the world. One of her works, “Brahmanda,” was selected for presentation at the first International Congress for Electroacoustic Music – Electroacoustic Winds 2015. The lecture will be held at the University of Aveiro, Portugal, on Sept. 17–20, 2015.