“There’s creativity everywhere,” says Michael Halassa. “But I think it’s amplified in the U.S., because of the diversity, because of how different everybody is, because of all the different points of view.” Altogether, Michael believes, this array of voices creates a chaotic but vibrant milieu that gives rise to some of the most innovative research in the world.

It isn’t something he takes for granted; Michael, a 2017 Vilcek Prizewinner for Creative Promise in Biomedical Science, was born in Jordan, at a time of political turmoil in the region, and he remembers watching religious radicalism take over public life. As a part of the religious minority, he was treated as a second-class citizen, and he never felt particularly welcomed in the country of his birth.

“Somehow, that translated to me feeling like I belonged to people who thought like me: scientists,” Michael says. In elementary school, his parents gave him a set of biographies of famous thinkers, such as Thomas Edison and Leonardo da Vinci. He became hooked on the elegance and precision of their thinking—and, by extension, math and science.

In an education system that encouraged practical career planning, Michael started medical school at the age of 16. While he found that he missed math, science, and deductive reasoning, he discovered a love of neuroscience, and he was especially fascinated by one of its central mysteries: How could electrical activity in a physical system, like the brain, give rise to a qualitative experience? Or, put into Michael’s words: “The idea that matter can become imagination, through some magical transformation.”

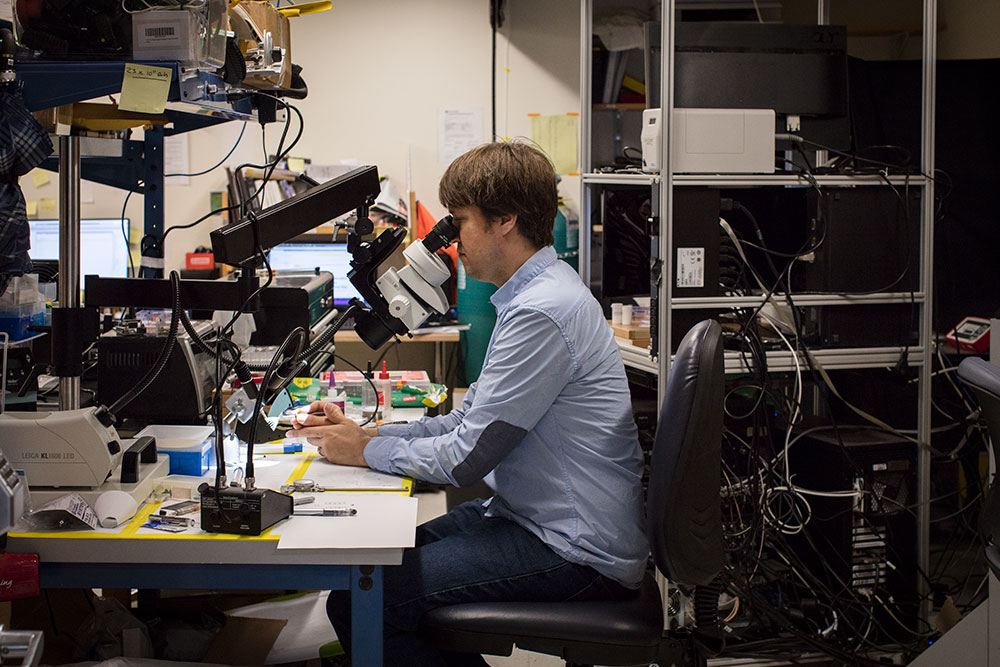

Thanks to Michael’s research, we may be pulling back the curtain on that magical transformation soon enough. After finishing medical school at the University of Jordan, Michael completed a doctorate at the University of Pennsylvania, and a residency and fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital. Today, he is an assistant professor of neuroscience at New York University, where he studies the role of the thalamus in maintaining attention and perception.

While neuroscience has made many advances in understanding the brain’s cortex—its folded, outer regions—not much is known about the thalamus, the small, egg-shaped structure that lies at the center of the brain. Through pioneering experimental models with mice, however, Michael’s lab demonstrated that the thalamus acts as a tunable sensory filter for external stimuli, enabling attention and perception.

“Imagine that you’re sitting at a dinner table,” Michael says. “I’m having a conversation with you, but without me even noticing, you can eavesdrop on a different conversation elsewhere.” This is what attention is, Michael says: the ability to sample the environment internally—not by changing our position, but by changing how loud a conversation is, perceptually, to ourselves.

He found that a group of brain cells within the thalamic reticular nucleus, or TRN, are vital to this process, and that they are also part of a mechanism that enables the brain to switch from relaying information from the outside world to inwardly focused processes, like thought and memory consolidation.

Working with a longtime friend and colleague, MIT neuroscientist Guoping Feng, Michael found that when the gene PTCHD1 is missing or damaged in mice, TRN is shown to be less capable of suppressing auditory signals. This gene has been implicated in people with autism or ADHD, and could explain their pronounced sensitivity to noise, which could form the basis for future treatments.

Beyond their therapeutic implications, Michael’s discoveries could also reveal a lot about that magical aspect of the mind itself. “My lab is really keen on understanding how these processes work,” he says, “because they’re informative of the human condition. It does go, to some degree, to our understanding of the stuff that makes the world real and possible in our heads.”